Bidding home page, with links to related pages

The cwinten | quintain is said to have been used as part of the activities at the house of a bride to occupy the goom’s men before they declaimed their pwnco and attempted to capture the bride. It might have been like the mediaeval tournament, surviving as a popular passtime at special events. The word became associated with a rope tied across the path of the bride and groom after the wedding to prevent them going to the wedding feast until they paid a toll.

It is clear from the following that many of the later descriptions were not based on first-hand observation but on earlier publications.

The word quintain, (cwinten, cwintyn, gwyntyn, cwyntyn, pleural: cwyntynau, gwyntynau) derives from Middle English quintaine, taken from Old French, derived from Latin quīntāna, “fifth”, in reference to a street between the fifth and sixth maniples of a Roman camp, where warlike exercises took place.

It was a game at tournaments in which a horseman with a lance attempted to hit a target which pivoted on a post and tried to avoid being hit by a weight (a bag of sand) at the other end of the pivot. It was used in mediaeval times as training for jousting and as a game in England until the 18th century. (Wikipedia)

A quintain was also a rope decorated with plants, flowers, ribbons, &c., spanning the road along which wedding party passed, &c., but latterly simply a plain rope used to hold up the car in which a newly-wedded couple travels, leave to proceed being given on payment of a sum of money.

Geiriadur Pryfysgol Cymru citing NLW Llanstephan, 1722; Walters, 1780; [Hughes], 1823 (below)

Postyn (wedi ei osod i sefyll yn y ddaear) a ddefnyddid gynt gan filwyr i briofi eu medr naill ai drwy ei daro â gwaywffyn nes eu torri neu drwy ymosod ar ddelw, sach dywod, etc, a grogid wrtho; yn ddiweddarach daeth yr arfer yn fath o ddifyrrwch neu chwarae cyffredinol ar achlysur priodas; twrnamaint

A post (set to stand in the ground) formerly used by soldiers to test their skill either by hitting it with spears until they were broken or by attacking a statue, sandbag, etc, that were hung at it; later the practice became a form of general amusement or play on the occasion of marriage; tournament.

Geiriadur Pryfysgol Cymru citing Salesbury, 1574; Owen (Pugh), 1794, below.

Illustrations

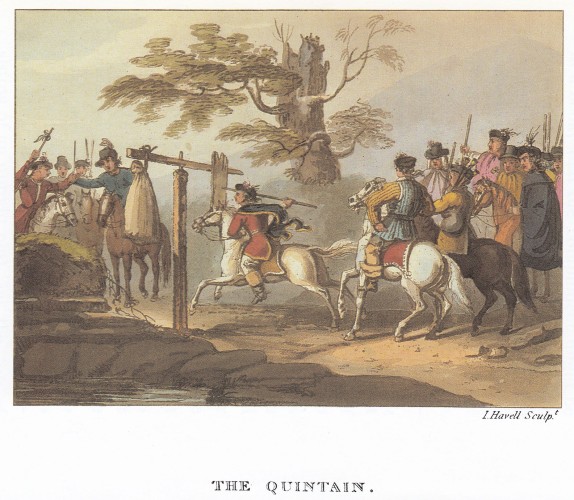

‘The Quintain’, J Havell, Sculp, Peter Roberts, Cambrian Popular Antiquities, (1815), opp. p. 163

Y Gwyntyn, Anon, [Hugh Hughes], Yr Hynafion Cymreig: neu, Hanes am draddodiadau, defodau, ac ofergoelion, yr Hen Gymru … (Caerfyrddin, 1823, based on the illustration in Peter Roberts’ book, on which Hughes’ text was mostly based.

Y Gwyntyn, Anon, [Hugh Hughes], Yr Hynafion Cymreig: neu, Hanes am draddodiadau, defodau, ac ofergoelion, yr Hen Gymru … (Caerfyrddin, 1823, based on the illustration in Peter Roberts’ book, on which Hughes’ text was mostly based.

Detail of a print by J. C. Rowland, ‘Welsh Wedding, Running away with the bride’, published by T. Catherall, (Chester and Bangor), 1850

This shows a quintain in the background.

1507

It is said that the first great mediaeval tournament held Wales (and the last in Britain) was organised by Sir Rhys ap Thomas at Carew Castle (Pembrokeshire) in April 1507.

When they had dined they went to visitt each Captaine in his quarter, where they found everie man in action, some wrestling, some hurling of the barr, some tossing of the pike, some running at the quinteine, everie man striving in a friendlie emulation to performe some act or other, worthie the name of Souldier.”

Anon, Biography of Rhys ap Thomas (from a ms. of c. 1610), Cambrian Register, (1796), p. 132

Prichard, Thomas Jeffery Llewelyn, Welsh Minstrelsy: Containing The Land Beneath the Sea, Or, Cantrev y Gwaelod, A Poem in three Cantos; with various other Poems, (London, 1824), pp. 53, 287-288

Nicholas, Thomas, Annals and Antiquities of the Counties and County Families of Wales, Volume 2, (1872), pp. 857-858

1547

Chwintyn i daro wrthei, a quyntyne

(Chwintyn to strike, and quyntyne)

Salesbury, William (ed.) A Dictionary in Englyshe and Welshe, (1547) [GPC]

Chwintan, chwintyn might be the root of Quintain according to Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, Heli Pitkänen, (2002), p. 194 who used this definition as their evidence.

1575

When Queen Elizabeth I visited Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, home of the Earl of Leicester, in July 1575, for example, among the entertainments put on for her, ranging from fireworks to feasting, was a “country bryde ale” that included a bride and bridegroom picked from the local peasants, the traditional wedding sport of “running at the Quinting” or quintain, that is, tilting on horseback with lances at a pole set into the ground, and “Morrice dancing”.

[Queen Elizabeth I visited Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, in July 1575]

On Sunday, opportunely, the weather broke up again; and after divine service in the parish church for the sabbath-day, and a fruitful sermon there in the forenoon : At afternoon, in worship of this Kenilworth Castle, and of God and Saint Kenelm, whose day, forsooth, by the Calendar this was, a solemn bridal of a proper couple was appointed : Set in order in the tilt-yard, to come and make their show before the Castle in the great court, where was pight a comely Quintain for feats at arms, which when they had done, to march out at the northgate of the Castle homeward again into the town.

And thus were they marshalled. First, all the lusty lads and bold bachelors of the parish, suitably habited every wight, with his blue buckram bride-lace upon a branch of green broom (because rosemary is scant there) tied on his left arm, for on that side lies the heart; and his alder pole for a spear in his right hand, in martial order ranged on afore, two and two in a rank : Some with a hat, some in cap, some a coat, some a jerkin, some for lightness in doublet and hose, clean truss’d with points afore; Some boots and no spurs, this spurs and no boots, and he again neither one nor other: One had a saddle, another a pad or a pannel fastened with a cord, for girthis were geazon : And these, to the number of sixteen wights, riding men and well beseen : But the bridegroom foremost in his father’s tawny worsted jacket, (for his friends were fain that he should be a bride-groom before the Queen) a fair straw hat with a capital crown, steeple-wise on his head ; a pair of harvest gloves on his hands, as a sign of good husbandry; a pen and inkhorn at his back, for he would be known to be bookish: lame of a leg that in his youth was broken at foot-ball; well beloved of his mother, who lent him a new muffler for a napkin, that was tied to his girdle for losing it. It was no small sport to mark this minion in his full appointment, that, through good tuition, became as formal in his action as had he been a bride-groom indeed; with this special grace by the way, that ever as he would have framed to himself the better countenance, with the worst face he looked.

Well, Sir, after these horsemen, a lively morrice-dance according to the ancient manner: six dancers, maid-marian, and the fool. Then three pretty pucelles, as bright as a breast of bacon, of thirty years old a-piece; that carried three special spice-cakes of a bushel of wheat (they had by measure, out of my Lord’s bakehouse) before the bride, Cicely, with set countenance and lips so demurely simpering, as it had been a mare cropping of a thistle. After these, a lovely loober-worts, freckle-faced, redheaded, clean trussed in his doublet and his hose, taken up now indeed by commission, for that he was loath to come forward, for reverence belike of his new cut canvas doublet; and would by his good will have been but a gazer, but found to be a meet actor for his office; that was to bear the bride-cup, formed of a sweet sucket barrel, a fair turn’d foot set to it, all seemly besilvered and parcell gilt adorned with a beautiful branch of broom, gaily begilded for rosemary: from which two broad bride-laces of red and yellow buckram begilded, and gallantly streaming by such wind as there was for he carried it aloft: this gentle cup-bearer had his freckled physiognomy somewhat unhappily infested, as he went, by the busy flies, that flocked about the bride-cup, for the sweetness of the sucket that it savoured of; but he, like a tall fellow, withstood their malice stoutly-see what manhood may do-beat them away, killed them by scores, stood to his charge, and marched on in good order.

Then followed the worshipful bride, led, after the country manner, between two ancient parishioners, honest townsmen. But a stale stallion and a well spread (hot as the weather was,) God wot, and ill-smelling was she: thirty years old, [or 35] of colour brown-bay, not very beautiful indeed, but ugly, foul, and ill-favored; yet marvelous fond of the office, because she heard say she should dance before the Queen, in which feat she thought she would foot it as finely as the best : Well, after this bride there came, by two and two, a dozen damsels for bride-maids, that for favour, attire, for fashion and cleanliness, were as meet for such a bride as a tureen ladle for a porridge-pot : More, but for fear of carrying all clean, had been appointed, but these few were enough.

As the company in this order were come into the court, marvellous were the martial acts that were done there that day. The bride-groom, for pre-eminence, had the first course at the Quintain, and broke his spear with true hardiment; but his mare in her manege did a little so titubate, that much ado had his manhood to sit in his saddle, and escape the foil of a fall; With the help of his hand, yet he recovered himself, and lost not his stirrups (for he had none to his saddle,) had no hurt as it happened, but only that his girth burst, and lost his pen and inkhorn which he was ready to weep for : but his handkercher, as good hap was, found he safe at his girdle: that cheered him somewhat, and had good regard it should not be soiled. For though heat and cold had upon sundry occasions made him some times to sweat, and sometimes rheumatic, yet durst he be bolder to blow his nose and wipe his face with the flappet of his father’s jacket, than with his mother’s muffler : ’tis a goodly matter, when youth are mannerly brought up, in fatherly love and motherly awe.

Now, Sir, after the bride-groom had made his course, ran the rest of the band a while in some order ; but soon after, tag and rag, cut and long tail: where the specialty of the sport was, to see how some for their slackness had a good bob with the bag; and some for their haste, too, would topple downright, and come down tumbling to the post : Some striving so much at the first setting out, that it seemed a question between the man and the beast, whether the course should be made on horseback or on foot: and put forth with the spurs, then would run his race by as among the thickest of the throng, that down came they together, hand over head : Another, while he directed his course to the quintain, his jument would carry him to a mare among the people; so his horse was as amorous, as himself adventurous: Another, too, would run and miss the quintain with his staff, and hit the board with his head.

Many such frolicsome games were there among these riders; who, by and by afterwards, upon a greater courage, left their quintaining, and ran at one another. There to see the stern countenances, the grim looks, the courageous attempts, the desperate adventures, the dangerous curvets, the fierce encounters, whereby the buff at the man, and the counterbuff at the horse, that both sometimes came topling to the ground : By my troth, Master Martin; ’twas a lively pastime; I believe it would have moved a man to a right merry mood, though it had been told him that his wife lay dying.

Note in the 1821 edition:

A comely Quintain. In the Glossary to Bishop Kennet’s Parochial Antiquities, it is stated that the Quintain was a customary sport at weddings. It consisted of an upright piece with a cross piece, one end of which is broad, and pierced full of holes, and to the other is appended a bag of sand, which swings round upon the slightest blow. “The pastime was,” says Hasted, “for the youth on horseback to run at it as fast as possible, and hit the broad part in his career with much force. He that by chance hit it not at all was treated with loud peals of derision; and he who did hit it, made the best use of his swiftness, lest he should have a sound blow on his neck from the bag of sand, which instantly swang round from the other end of the quintain. The great design of this sport was to try the agility of the horse and man, and to break the board, which whoever did, he was accounted chief of the day’s sport.”

[Robert] Laneham’s Letter Describing the Magnificent Pageants Presented Before Queen Elizabeth at Kenilworth Castle in 1575, (1821), pp. 27-34 and note on p. 100

Strype, Annals of the Reformation, vol. 2,

Brand, Popular Antiquities, (1841), p. 101

1617

[a sport held every fifth year among the Olympic games, or on the fifth or last day of the Olympics]

[a quintaine or quintelle, a game in request at marriages, when Jac and Tom, Dick, Hob and Will, strive for the gay garland.

Minsheu, The Guide into Tongues, p. 301

1640

At quintin he,

In honour of his bridal-tee,

Hath challenged either wide countee.

Johnson, Ben, (1572 – 1637), Underwood, (1640)

1656

Quintain: a Game or Sport still in request at Marriages, in some parts of this Nation, specially in Shropshire: the manner, now corruptly thus, a Quintin, Buttress, or thick Plank of Wood, is set fast in the Ground of the High-way, where the Bride and Bridegroom are to pass; and Poles are provided ; with which the young Men run a Tilt on horseback, and he that breaks most Poles, and shows most activity, wins the Garland.

Blount, Thomas, Glossographia (1656); (5th edition, 1681)

1677

- After what concerns women solitarily consider’d, who according to the courtesie of England, have always the first place, come we next to treat of things unusual that concern women and men joyntly together; amongst which I think we may reckon many ancient Customs still retained here, abolish’d and quite lost in most other Counties: such as that of Running at the Quinten, Quintain, or Quintel, so called from the Latin [Quintus] because says Minsheu, it was one of the Ancient Sports used every fifth year amongst the Olympian games, rather perhaps because it was the last of the [Greek] or the quinque certamina gymnastica, used on the fifth or last day of the Olympicks. How the manner of it was then I do not find, but now it is thus.

- They first set a Post perpendicularly into the ground, and then place a slender piece of Timber on the top of it on a spindle, with a board nailed to it on one end, and a bag of sand hanging at the other; against this board they anciently rod with spears; now as I saw it at Deddington in this County [Oxfordshire], only with strong staves, which violently bringing about the bag of sand, if they make not good speed away it strikes them in the neck or shoulders, and somtimes perhaps knocks them from their horses ; the great design of the sport being to try the agility both of horse and man, and to break the board, which whoever do’s, is for that time accounted Princeps Juventutis.

- For whom heretofore there was some reward always appointed, Eo tempore (says Matthew Paris) Juvenes Londinenses, statuto Pavone pro bravio, ad stadium quod Quintena vulgariter dicitur, vires proprias, & Equorum cursus, sunt experti: Wherein it seems the Kings servants opposing them were sorely beaten; for which, upon complaint, the King fined the City. Whence one may gather that it was once a tryal of Man-hood between two parties; since that, a contest amongst friends who should wear the gay garland, but now only in request at Marriages, and set up in the way for young men to ride at as they carry home the Bride, he that breaks the board being counted the best man.

Plot, Robert, The Natural History of Oxfordshire, (1677), pp. 200-201

1686?

eye-witness to quintains in Oxfordshire

Spelman, Henry, [1564?-1641?] Glossary, (1686) (in Latin)

1686-1687

The Quintin.

Riding at ye Quintin (in French Quintaine) at Weddings was used by the ordinary sort (but not very common) till the breaking-out of the Civil-warres. When I learned to reade I sawe one at a Wedding of one of ye Farmers [?] at Kington-St. Michael; it is performed at a crosse way, and it was there by the pound, and ’twas a pretty rustique sport. See the Masque of ….. in Ben: Johnson, where there is a livelie / perfect description of this custome.

There is a figure here to which the following description refers:

b is a Roller (for corne) pitched on end in some crosse way, or convenient place by which the Bride is brought home.

a, a leather Satchell filled wh Sand.

c, at this end, the young fellowes that accompany the Bride, doe give a lusty bang with their truncheons, which they have for this purpose, and if they are not cunning at it and nimble, the Sand-bag takes ’em in ye powle, and makes them ready to fall from their horses.

c, c, is a piece of wood about an ell long that turnes on the pinne of the Rowler,

e. When they make their stroke they ride a full career.

It seemes to be a remainder of the Roman Palus. v. Juvenal, satyr vi. v. [247-249.]

Aubrey, J., Remains of Gentilisme and Judaism, Lansdowne mss; ed. J. Britten (London, 1881)

1695 (published 1818)

Refers to Matthew Paris (pre 1253); Robert Plot (1677); Dr Watts; Henry Spelman, Giraldus Cambrensis (????);

The Quintain was a customary sport at weddings. It consisted of an upright piece with a cross piece, one end of which is broad, and pierced full of holes, and to the other is appended a bag of sand, which swings round upon the slightest blow.

[He said it was practiced at Blackthorne, and at Deddington, in Oxfordshire according to Brand, 1813.]

Kennett, White, (Bishop), Parochial Antiquities, Attempted in the History of Ambrosden: Burcester, and other adjacent Parishes in the Counties of Oxford and Bucks with a Glossary of Obsolete Terms, vol. 1, Chapter 6, ‘Roman Customs’, (1695), (1818), pp. 24-30

1722 WELSH

cwinten, math ar ddifyrrwch mewn prïodasau d.g. a quintain.

quinten, a form of amusement at weddings

NLW, Llanstephan MS 189i & ii, Llst 6

A manuscript containing ‘Lexicon Cambro-Britannicum’ by William Gambold, late of Exeter College, Oxford, later rector of Puncheston in Pembrokeshire. Part i of the manuscript contains an English-Welsh dictionary of ’88 sheets, writ in 7 months’ and completed ‘Sep. 14. 1722’. The material was ‘collected out of Dr. Davies’s Latin-Welsh Dictionary, the Welsh translation of the holy Bible, several approved Welsh Authors, and common use’. Part ii contains a Welsh-English dictionary of ’36 sheets’, begun ‘Nov. 27. 1721’ and completed ‘Feby. 17th 1721/2’

1722

The quintain consisted of a high upright post, at the top of which was placed a cross piece on a swivel, broad at one end and pierced full of holes, and a bag of sand suspended at the other. The mode of running at the quintain was by an horseman full speed and striking at the broad part with all his force; if he missed his aim he was derided for his want of dexterity ; if he struck it and the horse slackened pace, which frequently happened through force of the shock, he received a violent blow on the neck from the bag of sand which swung round from the opposite end; but if he succeeded in breaking the board he was hailed the hero of the day.

The last and indeed only instance of this sport which I have met with in this county was in 1722, on the marriage of two servants at Brington, when it was announced in the Northampton Mercury that a quintain was to be erected on the green at Kingsthorp, and the reward of the horseman that splinters the board is to be a fine garland as a crown of victory, which is to be borne before him to the wedding house, and another is to be put round the neck of his steed; the victor is to have the honour of dancing with the bride, and to sit on her right hand at supper.

Baker’s The History And Antiquities of the County of Northampton, (1822-1830), vol. 1, p. 41

Strutt, Joseph, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, (1903), new edition, pp. 105-112

1725

Henry Bourne made no mention of the Quintain.

Bourne, Henry, Antiquitates Vulgares (1725)

Mid 1760s

Lewis Morris who wrote one of the earliest detaild accounts of Welsh wedding customs, made no mention of the Quintain.

NLW ms 13226C, pp. 313-326; The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1791 and 1792

1769

This sport [quintain] is still practised at weddings among the better sort of freeholders in Brecknockshire; and as it differs a little from that of other countries, it may not be amiss to describe the manner of it here. On the morning of the nuptials, the bridegroom, attended by a large company of his relations and friends on horseback, goes to fetch his bride at her father’s house, and thence escorts her to church, accompanied by another party of her relations and friends. After the ceremony is over, on their way home to the bridegroom’s, a spot is chosen near the road side, where a few flat planks about six feet high are erected side by side. Long thick sticks are then distributed to each of the young men who are inclined to enlist in the sport. They grasp these sticks near the middle, resting one end of it under the arm; and thus they ride full speed towards the planks, striking the stick against them with the utmost force in order to break it, where the diversion ends. We know not precisely how the Romans practised the Quintain, but it is supposed to have obtained that name from Quintus, because it was repeated every fifth year among the Olympic games. It is still practised in many places both in France and other countries [?] … Plot [History of Oxfordshire, Chapter 5, section 22, 53], who likewise considers it of Roman origin, describes the manner of it in Oxfordshire, which exactly corresponds with the account which Sir Henry Spelman [Glossary] gives, who was an eye-witness. It is still practised, though differently, about Caermarthen (the ancient Maridurum of the Romans), so that Dr. Kennet’s observation [that he never saw Quintain used except where the Romans had been] may be esteemed in general true. Since, therefore, we trace the footsteps of the Romans in this sport, the prevalence of it in Brecknockshire, where we have other evident marks of them, seems a circumstance not unworthy notice.

Strange, John, ‘An Account of some Remains of Roman and other Antiquities in and near the Town of Brecknock, in South Wales’, in a letter read 13 and 20 April, 1769, Archaeologia of Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Second Edition, vol. 1, (1779), pp. 305-306

Quoted in Belgravia, An Illustrated London Magazine, vol. 38, (1879), p. 317

1780 WELSH

cwinten d.g. quintain, or quintin (a kind of game, or trial of strength and skill, to be seen at country-weddings, &c. where-in the hero on horse-back runs his rustic lance, i.e. a stake a tilt against a post and breaks it; or, if not, stands a fair chance of being unhorsed in the attempt, to the no small entertainment of the spectators).

Walters, John, English-Welsh Dictionary, (1780, 1828)

1782

On Offham green [Kent], there stands a Quintain, a thing now rarely to be met with, being a machine much used in former times by youth, as well to try their own activity, as the swiftness of their Horses in running at it. (He gives an engraving of it.) The Cross-piece of it is broad at one end, and pierced full of Holes; and a Bag of Sand is hung at the other, and swings round on being moved with any blow.

The pastime was for the youth on horseback to run at it as fast as possible, and hit the broad part in his career with much force. He that by chance hit it not at all was treated with loud peals of derision; and he who did hit it, made the best use of his swiftness, lest he should have a sound blow on his neck from the bag of sand, which instantly swang round from the other end of the quintain. The great design of this sport was to try the agility of the horse and man, and to break the board, which whoever did, he was accounted chief of the day’s sport.

It stands opposite the dwelling house of the Estate, which is bound to keep it up.

The same author, Ibid. p. 639. speaking of Bobbing parish, says : “there was formerly a Quintin in this parish, there being still a Field in it, called from thence the Quintin-Field.”

Hasted, History of Kent, (1782) vol. 2, p. 224; (2nd edition, 1797)

From Brand, (1813)

1794

Chwintan, (chwin – tan) a hymeneal game thus acted: A pole is fixt in the ground, with sticks set about it, which the bridegroom and his company take up, and try their strength and activity in breaking them upon the pole.

Owen (Pugh), W., (ed.) A Welsh and English Dictionary, (1794), (2nd edition 1832)

1798 WELSH

Quintain: math o chwarae, cwinten

(Quintain, type of game)

Richards, William, Geiriadur Saesneg a Chymraeg: An English and Welsh Dictionary, (1798)

1813

All Hallow Even

The Quintain seems to have been used by most nations in Europe. [Brand then lists a number of sources in England and Europe]

Brand, J., Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, vol. 1 (1813), p. 301

John Brand, Observations on Popular Antiquities …, Arranged, revised and greatly enlarged by Henry Ellis, (3rd edition, 1853), vol. 2, p. 436

1813

Sports at Weddings

Quotes the following:

letter describing the ceremony at Kenilworth in 1575

the Glossary in Bishop Kennet’s Parochial Antiquities (1695)

Blount’s Glossographia, v. quintain, 1681

Aubrey’s Remains of Gentilisme and Judaism 1686-1687

Hasted, History of Kent, (1782)

Owen, Welsh Dictionary, 1794

For an account of the QUINTAIN as a more general Sport, see vol. i. p. 301.

Brand, J., Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, arranged and revised with additions by Henry Ellis, vol. 1 (1813), vol. 2, pp. 84-86

Brand, J., Popular Antiquities of Great Britain with very large corrections and editions by Sir Henry Ellis, (1877), vol. 2, p. 395

1815

The friends of the bride in the mean time raised various obstructions, to prevent their access to the house of the bride, such as ropes of straw across the road, blocking up the regular one, &c., and the Gwyntyn, (literally the Vane), corrupted in English into Quintain, consisting of an upright post, on the top of which a spar turned freely. At one end of this spar hung a sand-bag, the other presented a flat side. The rider in passing struck the flat side, and if not dexterous in passing was overtaken, and perhaps dismounted by the sand-bag and became a fair object of laughter. The Gwyntyn was also guarded by the champions of the other party; who, if it was passed successfully, challenged the adventurers to a trial of skill at one of the twenty-four games; a challenge which could not be declined; and hence to guard the Gwyntyn was a service of high adventure.

… Whether the Gwyntyn, or Quintain, was in use among the Romans, I am not certain, though I rather think not. The name is, I think, with the learned [unnamed] author of the manuscript above mentioned, decisively of Welsh origin; and, in the custom of guarding the Quintain, the origin of the stories in romance, in which a knight guards a shield hung on a tree against all adventures, is clearly perceived.

Illustration of ‘The Quintain’ by J Havell

Roberts, Peter, The Cambrian Popular Antiquities: or, An account of some traditions, customs, and superstitions, of Wales, with observations as to their origin, &c. &c., (1815), pp. 162-166

1818

This extract is from a long article by a Welsh vicar, Eliezer Williams, (1754-1820). He was born in Pibwr-lwyd, Llangynnwr, Carmarthenshire and was vicar of Cynwyl Gaeo with Llansawel, Carmarthenshire, 1784-1799 and later, vicar of Lampeter, Ceredigion where he ran a grammar school for 14 years. The article was entitled An Historical Essay on the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Celtic Tribes, particularly their Marriage Ceremonies and was mostly derived from Samuel Meyrick’s The History and Antiquities of Cardigan, (1808, 1810), pp. cxxviii-cxlvi and Cambrian Popular Antiquities, (1815). He included a brief comment at the end, lamenting the loss of such customs in his time; the adoption of English conventions and the unfounded criticisms of Welsh weddings which had been recently published. He also praised the custom of supporting the newly married couple with bidding loans.

The attendants of the bride were in constant expectation of their approach, and the most active of them made every preparation to frustrate their designs, and disappoint their hopes. Every difficulty was early opposed to them, and every method not deemed dishonourable taken to obstruct them in their rout and impede them in their career. Straw ropes were fastened across the road, five-barred gates placed at intervals in the way, and where a passage was practicable through a river, the road was completely blocked up, that the youthful adventurers might at once discover their dexterity and excellence in horsemanship and swimming, the two most enterprising of the four-and-twenty games. The most formidable of the difficulties, however, invented to impede the progress of the adventurers in their rout was the “Gwyntyn,” which anciently consisted of an upright post, on the top of which a cross bar turned on a pivot; at one end of the cross bar hung a heavy sand bag, and at the other was placed a broad plank; the accomplished cavalier in his passage couched his lance, and with the point made a thrust at the broad plank, and continued his rout with his usual rapidity, and only felt the gwyntyn, or the air of the sand bag, fanning his hair as he passed. [note: Cambrian Popular Antiquities, p. 163.]

Hence this dangerous machine was denominated the “gwyntyn,” and in process of time corrupted into the vulgar and well known expression of “quintin.” The awkward horseman in attempting to pass this terrific barrier, was either unhorsed by the weight of the sand-bag, or by the impulse of the animal against the bar found his steed sprawling under him on the ground. At no great distance from every obstacle designedly thrown in the way, a party was stationed to wait the expected events, and deride the fallen riders, as well as those who unnecessarily attempted feats that required more consummate skill, and a greater share of agility than they could justly boast of. All who proved unsuccessful were considered as fair objects of ridicule, because no person was compelled to engage in these arduous enterprises, and no motive but unjustifiable vanity could induce men who knew themselves to be unequal to the task, to place themselves on the list of accomplished champions, who had valour to undertake and abilities to execute the most arduous difficulties and the most hazardous enterprizes.

“Ludere qui nescit campestribus abstinet armis,

Indoctus pile, discive, trochive quiescit,

Ne spissa risum tollunt impune corone.”

– “One that cannot dance, or fence, or run,

Despairing of success, forbears to try.”

Those who thus insulted fallen and unsuccessful adventurers, were expected, if called upon, to perform themselves the feats which they derided others for attempting in vain; and it was reckoned base and dishonourable to oppose to others difficulties which they could not themselves surmount. The “gwyntyn” was guarded by the most accomplished champions of the party, for they were obliged, if called upon, to pass it themselves at full career, and if challenged by one of the adventurers, they were required to contend with them at one of the four-and-twenty games, and if vanquished became themselves the objects of raillery and popular invective. Hence “cadw gwyntyn,” or to guard a quintin, was esteemed a most formidable enterprise.

Anon [Williams, Eliezer, [1754-1820], ‘An Historical Essay on the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Celtic Tribes, particularly their Marriage Ceremonies’, Cambrian Register, vol. 3, (1818), pp. 59-86

Williams, Eliezer, [1754-1820], The English Works of the Late Rev. Eliezer Williams, vicar of Lampeter and Caio Cwm Llansawel, … With a Memoir of his Life by his son, Saint George Armstrong Williams, (London, 1840), pp. 23-42, to which his son added some lengthy notes.

1823

GWYNTYN

Y mae rhai gweddillion o’r hen gamp hon i’w canfod hyd y dydd heddyw yn mhriodasau y Cymry.

Bydd ai cyfeillion y briodas-ferch mewn dysgwyliad gwastadawl am eu dyfodiad, a’r rhai mwyaf calonog o honynt a wnelent bob parotöadau i’w rhwystro yn eu bwriadau, ac i siomi eu gobaith. Gosodid pob rhwystrau yn eu ffordd, a defnyddid pob moddion na chyfrifd yn ddianrhydeddus, i’r dyben o’u gwan-galoni, ac i brofi eu gwroldeb a’u medrusrwydd mewn marchwriaeth; ac un o’r rhwystrau a ddefnyddid fynychaf ar yr achlysuron hyn oedd y “Gwyntyn.”

[nodyn] Am ddesgrifiad cyflawn o’r “Gwyntyn,” gwel “Marchogaeth,” yn mysg Campau yr hen Gymry. [diwedd y nodyn]

Gorau graith i lewddyn

Pa gyntaf êl trwy’r Gwyntyn;

Ei farch dewr, cyflym, yn ddinâg

A’i ceidw rhag y cwdyn.

(Some remains of this ancient sport can still be found today in Welsh weddings.

Either the friends of the bride-to-be will be in constant anticipation of their arrival, and the most heartfelt of them would do all preparations to hinder them in their intentions, and to disappoint their hope. All obstacles were set in their way, and every medicine or count was honourably used, to the end of their weak-heartedness, and to prove their courage and skill in riding; and one of the most commonly used obstacles on these occasions was the “Gwyntyn“.

[note] For a complete transcript of the “Gwyntyn,” see “Marchogaeth,” among the Sport of the old Welsh. [end of note]

Best to a scarecrow

Which first goes through the Gwyntyn;

His brave, swift, dumb horse

And keep it from the bag.)

Anon, [Hugh Hughes] Yr Hynafion Cymreig: neu, Hanes am draddodiadau, defodau, ac ofergoelion, yr Hen Gymru … (Caerfyrddin, 1823), pp. 110-111, 125-13

This includes an illustration entitled ‘Y Gwyntyn’ opp. p. 11, see above

1824

Notes to Prichard’s ‘The Land Beneath the Sea’, Canto 2

The gambols of the village green-

The wedding-day hath there been kept,

A merry time! the bidder’s rhyme,

The quintain sport, the church bell chime,

The quintain sport, the church bell chime.

This, with many of the more noble sports, practiced at Weddings, in Wales, has long been discontinued. “It was a ludicrous and sportive way of tilting on horseback, at some mark hung on high, moveable, and turning round, which, while the riders strike at with lances, unless they ride quickly off, the versatile beam strikes upon their shoulders.”

Dr. Watts in Verbo Quintena.

Sir H. Spelman, [Henry Spelman [1564?-1641?] Glossary, (1686)] from being a spectator of it says, “It is a piece of board fixed at one end of a turning beam, and a bag of sand at the other, by which means, striking at the board whirls round the bag, and often dismounts the rider. It is supposed to be a Roman game, and left in this Island ever since their time.”

Among the sports at the princely fete given by Sir Rhys ap Thomas, at Carew Castle, in Pembrokeshire, [1506, 1507?] Quintain is thus named by his biographer. “When they had dined they went to visit each Captaine in his quarter, where they found everie man in action, some wrestling, some hurling of the bar, some taking of the pike, some running at the quintain, every man striving in a friendlie emulation to performe some act or other, worthie the name of Souldier.”

Prichard, Thomas Jeffery Llewelyn, Welsh Minstrelsy: Containing The Land Beneath the Sea, Or, Cantrev y Gwaelod, A Poem in three Cantos; with various other Poems, (London, 1824), pp. 53, 287-288

1830

Description a variety of Quintain games.

The use of the quintain survived in many parts of rural England in the eighteenth century, particularly as a wedding sport. The following passage from Baker’s The History And Antiquities of the County of Northampton, (1822-1830), vol. 1, p. 40 records its use in that county: “The quintain consisted of a high upright post, at the top of which was placed a cross piece on a swivel, broad at one end and pierced full of holes, and a bag of sand suspended at the other. The mode of running at the quintain was by an horseman full speed and striking at the broad part with all his force; if he missed his aim he was derided for his want of dexterity ; if he struck it and the horse slackened pace, which frequently happened through force of the shock, he received a violent blow on the neck from the bag of sand which swung round from the opposite end; but if he succeeded in breaking the board he was hailed the hero of the day.

The last and indeed only instance of this sport which I have met with in this county was in 1722, on the marriage of two servants at Brington, when it was announced in the Northampton Mercury that a quintain was to be erected on the green at Kingsthorp, ‘and the reward of the horseman that splinters the board is to be a fine garland as a crown of victory, which is to be borne before him to the wedding house, and another is to be put round the neck of his steed; the victor is to have the honour of dancing with the bride, and to sit on her right hand at supper.”

Strutt, Joseph, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, (1903), new edition, pp. 111-112

1835

CHWINTAN, (o chwin a tán,) math o chwareu a arferid gynt amser priodas, a hymeneal game. Dodid pawl mawr yn y ddaear, a ffyn o’i ddeutu, y rhai a gymerid, i fynu gan y priodfab a’i gyfeillion, i’r dyben i ddangos eu nerth a’u bywiogrwydd yn tòri y cyfryw ar y pawl unionsyth. Y mae llefydd o’r enw Pen y Chwintan mewn amryw fanau yn Nghymru.

(CHWINTAN, (from ??queen and FIRE?,) a type of play formerly used for wedding, and hymeneal game. A large pole was placed in the ground, and sticks around it, which were taken, up by the groom and his friends, to the end to show their strength and vitality in tormenting such on the upright pawl. There are places called Pen y Chwintan in various places in Wales.)

Williams, Owen, Welsh Encyclopedia: Y Geirlyfr Cymraeg, yr hwn sydd yn cynnwys Geiriadur Ysgrythyrol, Hanesol, ac Ieithyddol, Cyf. 1, (1835)

[Based on William Owen (Pugh)’s dictionary of 1794 and 1832]

1841

In our old forest laws, Scotale was the keeping of an ale house in the forest by the forester, with the power to compel people to spend their money there for fear of his displeasure, or in order that he might wink at their offences in the forest. But there appears to have been another kind, which was classed with the quintin, wrestling, and other rustic sports. Thus, in the inquisition of the Archdeacon of Lincoln is a query, (with a view to a prohibitory decree or ordinance), whether the people of the diocese raise quintains, make scotales, or wrestle when they go with the banner of mother church. What is it in this scotale which offended the clergy? I take it to have been the clubbing of money for liquor, quasi shot-ale, from the Saxon sceot, money, and ealo, ale.

In Cumberland they have a bydale, or bridal-feast, called the Bidden Wedding, which, says Houseman, “was very common a few years ago, and is not yet quite obsolete”.

Hampson, R.T., Medii Aevi Kalendarium: Or Dates, Charters, and Customs of the Middle Ages … , vol. 1, (1841), pp. 287-289

1855

Why is the game of quintain so called ?

Because it was invented by Quinetus or Quintas, “but who he was, or when he lived,” says Strutt, “is not ascertained. The game itself was a species of mock combat among the Romans, who caused the young military men to practise at it twice a day. From the Romans it descended to the Welch, who spell it gwyntyn, literally meaning vane. It was a bridal game: thus Ben Jonson says,

At quintin he,

In honour of his bridal-tee,

Hath challenged either wide countee.

Dr. Kennet, in his Parochial Antiquities, from Dr. Plot, says, that at the village of Blackthorn, through which the Roman road lay, they use it at their weddings to this day, on the common green, with much solemnity and mirth.” Dr. Plot also says, “it was set up in the way for young men to ride at, as they carry home the bride; he that breaks the board being counted the best man.”

Anon, The Book of Knowledge for All Classes, (1855), pp. 462-463

1856

On the day of the wedding, everyone was dressed in their best, a straw rope and a stone barricade were put up to prevent the bridegroom’s party from arriving and a gwyntyn had been erected.

Rodenberg, Julius, Ein Herbst in Wales, (1858)

Spalding, K., Gwerin, vol. 2, (1958-1959), pp. 41-43

Linnard, William (translator and editor), An Autumn in Wales, 1856: Country and People, Tales and Songs, (1985), pp. 142-152

Based on Peter Roberts, Cambrian Popular Antiquities, (1815) or Meyrick?

1859

Achlesid y gamp o farchogaeth hefyd er mwyn difyrwch, ac er mwyn hela. Enwn yma “Gwyntyn priodas” sydd eto heb ddiflanu yn hollol o rai parthau o Gymru, fel y gwelsom ein hunain. Rhwymir rheffyn gwellt yn groesi’r heol, o bost i bost, neu o lwyn i lwyn, fel bydd yn rhaid i’r gwyr ceffylau — rai ugeiniau o honynt yn yr hen briodasau dwl — neidio y “gwyntyn,” neu y “gwinten,” fel ei gelwir mewn rhai manau. Dywedir fod y gair “gwyntyn” yn dyfod o arferiad henach, sef y dodid pawl ar ganol y ffordd, a thrawst croes i’r heol yn troi ar y pawl; byddai astell ar un pen i’r trawst, a chwd yn llawn o dywod ar y pen arall; y marchogwr medrus a elai ar garlam gan daro yr astell â blaen ei waewffon er agor y rlordd, a chan gyflymu ym mlaen i ddianc rhag ergyd y pen arall, ac ni tbeimlai y medrus ond gwynt y cwd â’r tywod yn cyflymu ato. Byddai rhith ymladdau ar feirch ac efo ffyn yn beth tra arferol yn yr ben oesoedd. (Wynn’s History of the Gwydir Family)

The sport of riding was also pursued for amusement, and for hunting. We call here “Gwyntyn marriage” as yet we have not yet completely disappeared from some parts of Wales. Straw rope is bound across the road, from post to post, or bush to bush, so that the horsemen – some twenties of them in the old ?foolish marriages – will have to jump the “gwyntyn,” or the “gwinten”, as it is called in some places. It is said that the word “gwyntyn” came from an older custom, that a pole was placed in the middle of the road, and a cross beam on the road turned on the pole; there would be a board at one end of the beam, and a pouch full of sand at the other end; the skilful rider who was hurrying, hitting the bat with the tip of his spear to open the road, and speeding ahead to escape the blow of the other end, and the skilled felt only the wind of the kite and the sand speeding up. Virtual fights on horses and with sticks would be a thing of the past.

Anon, ‘Campau y Cymry’ (Welsh Sport), Y Brython, Cyf. 2 rhif. 11 (1859), t. 382-383

1866

Math ar chwareu bywiog (a chwareuid gyda phawl a ffyn ar ddyddiau priodas).

(Chwintan a sort of active game (played with pole and sticks on hymeneal days).)

Owen (Pughe), William, Geiriadur Cenhedlaethol Cymraef a Saesneg. A National Dictionary of the Welsh Language, 3rd edition edited and enlarged by Robert John Pryse, (1866).

1869

The game of quintain was a very usual adjunct to weddings in Wales in early times, and it was also common in England on similar occasions. … sometimes a quintain, which was rigidly guarded by the bride’s party, who challenged the opposite company to games with it. If the competitors, as they rode atilt at the flat side of the machine, were not dexterous, they were overtaken by the swinging sand-bag and struck off their horses—an occurrence which gave great pleasure to the woman’s champions, who maintained a friendly hostility to the man and his companions.

Owen, in his “Welsh Dictionary,” under the word “cwintan,” says: “A pole is fixed in the ground, with sticks set about it, which the bridegroom and his company take up, and try their strength and activity in breaking them upon the pole.” Ben Jonson refers to the quintain at weddings as follows:

“At quintin he,

In honour of his bridal-tee,

Hath challenged either wide countree.”

Wood, Edward J., The Wedding Day in All Ages and Countries, vol. 2, (London, 1869), pp. 80-88; (New York, 1869), pp. 190-200

1870

Yr oedd cwinten wedi ei gosod yn groes i’r ffordd rhwng y Pant a’r Eglwys.

A quintain had been placed opposite the road between Pant and the Church.

Yr oedd yn un fawr, gref, ac yn rhy frwnt i neb gwrdd â hi, a bu rhaid cael bilwg dwylaw cyn ei thori.

It was big, strong, and too dirty for anyone to meet, and it had to have a double billhook before cutting it.

Nid allodd neb neidio drosti ond Shemi Gallt yr odyn; aeth ef drosti fel barcutan.

No one could jump over her except Shemi of Gallt yr odyn; he went over her like a kite.

Dywedir mai Twm Penddol wnaeth y gwinten.

Twm Penddol is said to have made the quintain.

Davies, David (Dewi Emlyn, 1817-1888, editor of Baner America), [Fictitious] letters from Anna Beynon of Bargod, near Llandysul, to her sister in America, dated 1719-1727, Baner America, Awst 24, 1870 and other publications in Wales.

1870

In the reigns of our later Tudor sovereigns, weddings in Wales were often celebrated by tilting at the quintain, – an upright post, on the top of which a cross-piece turned upon a pin, at one end of which was a broad board, and at the other a heavy sand-bag. The play was to ride and strike the board with a lance, and pass off before the sand-bag, swinging round, should strike the tilter to the ground. “On the day of the marriage ceremony,” says Roberts, in his “Popular Antiquities of Wales,” the “nuptial presents having been made, and the marriage privately celebrated at an early hour, the signal to the friends of the bridegroom was given by the piper, who was always present on these occasions, and mounted on a horse trained for the purpose; and the cavalcade being all mounted, set off at full speed, with the piper playing in the midst of them, for the house of the bride; her friends in the meantime having raised various obstructions to prevent their access to her house, such as ropes of straw across the road, and the quintain. The rider, in passing, struck the flat side, and if not dexterous, was overtaken and perhaps dismounted by the sand-bag, and became a fair object for laughter.”

‘Sexagenarius’ A Handy Book of Matters Matrimonial, according to law and practice in Great Britain, (London, 1870), pp. 51-53

1878

The Quintain

Ben Johnson thus notices the quintin, quintain, or gwyntyn, as the Welsh spell it.

“At quintin he,

In honour of his bridal-tee,

Hath challenged either wide countree. …”

The word gwyntyn literally meant vane and was corrupted by the English into quintin or quintain. Thus, we may naturally suppose, that this ancient custom, and more particularly bridal game, was borrowed by the Britons from the Welsh, who had it from the Romans on their invasion of England. … At weddings, in England and Wales, it was a constant amusement, and so generally practiced in the latter country, that it may almost be said to class with their sports and manners.

(Quotation from Robert’s Popular Antiquities (1815), ‘On the day of the ceremony …)

Hone, William, The Table Book, of Daily Recreation and Information: … (1878), p. 534

1879

THE QUINTAIN.

My better parts

Are all thrown down; and that which here stands up

Is but a quintain: a mere lifeless block.

As You Like It, i. 2.

THOUGH in process of time the quintain became a mere pastime and a source of amusement both to player and spectator, it was originally strictly a military exercise, and occupied an important place in the severe course of schooling that the young aspirant to knighthood had to go through in feudal times. Almost as soon as the youth of gentle blood began to learn his page’s duty, he was set on horseback, and taught to ride at the ring, or to risk the sandbag and wooden sabre of the ‘Turk’s head quintain, till, from constant training of hand and eye, the young knight, by the time he had won his golden spurs, found it no very difficult matter to couch a lance in the lists, and to strike with true aim the helmet or shield of his opponent in the joust.

The quintain that tyros in chivalry originally practised at was nothing more than a trunk of a tree, or a post set up for the purpose; them a shield was fixed to this post, or often a spear was used, to which the shield was bound, and the tilters’ object was to hit this shield in such a way as to break the ligatures and bear it to the ground. ‘In process of time, says Strutt, “this diversion was improved, and instead of the staff and the shield, the resemblance of a human figure, carved in wood, was introduced. To render the appearance of this figure more formidable, it was generally made in the likeness of a Turk or a Saracen, armed at all points, bearing a shield upon his left arm, and brandishing a club or a Sabre with his right. Hence this exercise was called by the Italians “running at the armed man,” or “at the Saracen.” This is ‘the Turk’ of the old fifteenth century poet, whose apparently bloodthirsty lines read so strangely familiar to us after so much of the Eastern Question nowadays.

Lepe on thy foe; look if he dare abide.

Will he not flee? wounde him : make woundes wide;

Hew of his honde: his legge: his theyhs: his armys :

It is the Turk, though he be sleyn noon harm is.

In tilting at the Saracen, the horseman had to direct his lance with great adroitness—Strutt goes on to tell us—and make his stroke on the forehead of the figure, between the eyes, or on the nose; “for if he struck wide of these parts, especially upon the shield, the quintain turned about with much velocity, and, in case he was not exceedingly careful, would give him a severe blow upon the back with the wooden sabre held in the right hand, which was considered as highly disgraceful to the performer, while it excited the laughter and ridicule of the spectators.” The authorities are all at variance about the derivation of the Word quintain, as well as the source from which the exercise was introduced into Britain. Some say it was a Greek game named after its inventor Quintas, about whom mothing is known; equally absurd is the derivation of Minshew, who thinks it derives its name from Quintus, either because it was the last of the “pentathlon,” or because it was engaged in on the fifth, or last, day of the Olympic games; While sticklers for a home derivation seem to have agreed that it was a corruption of the Welsh “gwyntyn”, meaning a vane, till Dr. Charles Mackay recently published his book on the Gaelic etymology of the English language, and argued that the name of our pastime owes its origin to the Gaelic guin, which means to pierce.

Where doctors so differ it is unnecessary to say more than that an exercise something like quintain seems to have been in common use among the Romans, who caused their young military men to practise at it twice in the day, with weapons much heavier than those employed in actual warfare. Strutt points out that, in the code of laws compiled by the Emperor Justinian, the quintain is mentioned as a well known sport; and allowed to be continued upon condition that, at it, pointless spears only should be employed, contrary to the ancient usage, which, it seems, required them to have heads or points.

Dr. Kennett was so convinced of the Roman origin of the game that he says he never saw the quintain practised in any part of the country but where Roman ways ram, or where Roman garrisons had been placed.

While tyros in chivalry were practising hard at the Saracen to acquire skill, and older knights were charging it in the constant training needed to retain that skill, burgesses and yeomen began to adopt the quintain as a merry pastime, and village greens were beginning to resound with uproarious mirth as the staff or sandbag whirled round to belabour the clumsy rider who had failed to hit the proper part of the Turk’s forehead. What made the quintain such a favourite pastime of the common folk, was the rule of chivalry that forbade any person under the rank of an esquire to enter the lists as a combatant at tournament or joust. Accordingly, as the prohibition did not extend to the quintain, young men whose station debarred them from entering the lists set up a simple form of quintain on their village green, and, if they were not able to procure horses, contented themselves with running at this mark on foot. These village quintains—of which one specimen at least is still preserved, that of Offham, in Kent—consisted only of a cross bar turning on a pivot, with a broad end to strike against, while from the other extremity hung a bag of sand or earth, that swung round and hit the back of a lagging rider. A correspondent of ‘Notes and Queries‘ says that the Offham quintain is still in good order; had it not been that a road has been made to pass within a few feet of it, a man might ride at it now. The striking board is not perforated, that is, bored through, but some Small round holes about a quarter of an inch deep are cut on it, probably to afford a better hold for the lance, and to prevent its glancing off.

When many joined in running at the quintain, prizes were offered, and the winner was determined by the number and value of the strokes he had made. At the Saracen a stroke on the top of the nose counted three, others less and less, down to the foul stroke that turned the quintain round and disqualified the runner. It was at one of these prize gatherings that the unlucky incident took place that Stowe tells from Mathew Paris. In 1254, the young Londoners, who, the historian tells us, were very expert horsemen, met together one day to run at the quintain for a peacock, a bird very often in those days set up as a prize for the best performer. King Henry the Third’s Court being then at Westminster, some of his domestics came into the city to witness the sports. They behaved in a very disgraceful manner, and treated the Londoners with much insolence, calling them cowardly knaves and rascally clowns; conduct which the citizens resented by beating the king’s menials soundly. Henry, however, was incensed at the indignity put upon his servants, and not taking into consideration the provocation on their part, fined the city one thousand marks. ‘Some have thought these fellows were sent thither purposely to promote a quarrel, it being known that the king was angry with the citizens of London for refusing to join in the crusade.’

Stowe goes on to say that in London this exercise of running at the quintain was practised at all seasons, but more especially at Christmas time. “I have seen, continues the author of the ‘Survey of London,’ ‘a quintain set up on Cornhill by Leadenhall, where the attendants of the lords of merry disports have run and made great pastimes; for he that hit not the broad end of the quintain was laughed to scorn, and he that hit it full, if he rode not the faster, had a sound blow upon his neck with a bag full of sand hanged on the other end.”

Though running at the quintain was a common exercise at all festive gatherings of the country people, it was the especial exercise at marriage rejoicings.

Ben Jonson alludes to this when he writes of the bridegroom —

…. at quintin he,

In honour of his bridal-tee,

Hath challenged either wide countee.

Come cut and long taile, for there be

Six bachelors as bold as he,

Adjuting to his company;

And each one hath his livery.

Roberts, in his ‘Popular Antiquities of Wales’, gives this interesting account of the ancient marriage customs in the Principality:—‘On the day of the ceremony, the nuptial presents having previously been made, and the marriage privately celebrated at an early hour, the signal to the friends of the bridegroom was given by the piper, who was always present on these occasions, and mounted on a horse trained for the purpose; and the cavalcade being all mounted, set off at full speed, with the piper playing in the midst of them, for the house of the bride. The friends of the bride in the mean time having raised various obstructions to prevent their access to the house of the bride, such as ropes of straw across the road, blocking up the regular one, &c., and the quintain : the rider in passing struck the flat side, and if not dexterous, was overtaken, and perhaps dismounted, by the sandbag, and became a fair object for laughter. The gwyntym, was also guarded by champions of the opposite party, who, if it was passed successfully, challenged the adventurers to a trial of skill at one of the four-and-twenty games, a challenge which could not be declined; and hence to guard the gwyntyn was a service of high adventure.’

Lameham, in his ‘Progresses of Queen Elizabeth,” gives an amusing description of a ‘country bridal, which the virgin Queen witnessed when she was at Kenilworth in 1575. After the wedding there “was set up in the castle a comely quintane for feats at armes, where, in a great company of young men and lasses, the bridegroom had the first course at the quintane and broke his spear very boldly. But his mare in his manage did a little stumble, that much adoe had his manhood to sit in his saddle. But after the bridegroom had made his course, ran the rest of the band, a while in some order, but soon after tag and rag, cut and long tail; where the speciality of the sport was to see how some for his slackness had a good bob with the bag, and some for his haste to topple downright and come tumbling to the post; some striving so much at the first setting out that it seemed a question between man and beast, whether the race should be performed on horseback or on foot; and some put forth with spurs, would run his race byas, among the thickest of the throng, that down they came together, hand over head. Another, while he directed his course to the quintane, his judgment would carry him to a mare among the people; another would run and miss the quintane with his staff, and hit the board with his head.”

This interesting old wedding custom continued to be observed at marriages down to comparatively recent times. It is possible that it may still hold a place among the bridal rejoicings in the Principality; at any rate, Mr. John Strange, writing in 1796, (‘Archaeologia, vol. i. p. 303), says that “this sport is still practised at weddings among the better sort of freeholders in Brecknockshire;’ and then goes on to describe the variety of the pastime in use there—a few flat planks, erected on a green, against which the young men tilt with long thick sticks, ‘striking the stick against the planks with the utmost force in order to break it, where the diversion ends ; a variety of the quintain very like ‘the came game, at which Richard Coeur de Lion lost his temper on Sunday afternoon outside the walls of Messima in Sicily, while on his way to the Holy Land.

Mr. Anthony Trollope, in one of his Barsetshire novels, makes pleasant fun of old Miss Thorne’s attempt to revive the quintain at a rural féte; but, though the novelist makes dire disaster befall the old lady’s riders, the old pastime has sometimes been revived in real life, and with success. Indeed, as Mr. Bernhard Smith observes in ‘Notes and Queries’, the quintain is probably not so uncommon as is generally supposed. Mr. Smith has seen two— one at Chartley, Lord Ferrers’ seat in Staffordshire, and another in a riding house belonging to the late Mr. Harrington at his house near Crawley in Sussex. The ‘Times’ (August 7, 1827) had a long account of a revival of the old pastime, in which several varieties are described, and of which we may quote a part : ‘Viscount and Viscountess Gage gave a grand fête on Friday (August 3, 1827) at their seat at Firle-Place, Sussex, to about a hundred and sixty of the mobility and gentry, at which the ancient game of quintain was revived. The sports commenced by gentlemen riding with light spiked staves at rings and apples suspended by a string, after which they changed their weapons to stout poles, and attacked the two quintains, which consisted of logs of wood fashioned to resemble the head and body of a man, and set upright upon a high bench, on which they were kept by a chain passing through the platform, and having a weight suspended to it, so that if the log was ever struck full and forcibly the figure resumed its seat. One was also divided in the middle, and the upper part, being fixed on a pivot, turned, if not struck in the centre, and requited its assailant by a blow with a staff, to which was suspended a small bag of flour.

‘The purses for unhorsing this quintain were won by John Slater and Thomas Trebeck, Esqrs. The other figure, which did not turn, offered a lance towards the assailant’s face, and the rider was to avoid the lance and umborse the quintain at the same time. The purses were won by Sheffield Neave, Esq. and the Hon. John Pelham.

‘A third pair of purses were offered for unhorsing the quintain, by striking on a coloured belt, which hooped round the waist of the figure, thereby raising the weight, which was considerable, by a much shorter lever than when struck higher up. This was a feat requiring great strength and firmness of seat, and though not fairly won according to the rules of the game, the prizes were ultimately assigned to the very spirited exertions of Messrs. Cayley and Gardener.

Strutt notices a great many games akin to or derived from the quintain, of which perhaps the most interesting were the ‘Water Quintain, and “Running at the Ring.’

The boat quintain, and tilting at each other upon the water (a favourite pastime still at some sea-bathing places), were introduced by the Normans as amusements for the summer season, and were very soon established favourites among all classes of the people. Fitzstephen describes the exercise as practised by the Londoners of his day during the Easter holidays, when a pole was fixed in the Thames, with a shield strongly attached to it, towards which a boat, with the tilter standing in the bows, was Swiftly pulled. If the tilter’s lance struck the shield fairly and broke, all went well; but if otherwise, he was thrown into the water, greatly to the amusement of the people who crowded the bridges, wharves, and houses near the river, and ‘Who come,’ says the author, “to see the sports and make themselves merry.’

Stowe has often seen ‘in the Summer Season, upon the river of Thames, some rowed in wherries, with staves in their hands, flat at the fore end, running one against another, and for the most part one or both of them were overthrown and well ducked.” When Queen Elizabeth visited Sandwich in 1573, ‘certain wallounds that could well swim entertained her with a water tilting, in which one of the combatants ‘did overthrow another, at which the Queene had good sport.’

A much more important descendant of the quintain than this laughable pastime was Running at the Ring, a sport demanding all the skill of the quintain, but without its roughness and horseplay. Accordingly, we find that, while Giles and Hodge continued to urge their dobbins with unabated relish against the whirling board and sandbag, the Squire and the courtier transferred their attention to the more delicate exercise, and attained to high skill at it. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries “this generous exercise, as Whitelocke calls it, was reduced to a science, with minute rules and directions on all points of procedure and parts of the equipment necessary.

Randolph, in a letter from Scotland to Secretary Sir William Cecil on December 7, 1561, gives us an account of the pastime as celebrated at the Scottish Court of Queen Mary. He is reporting part of a conversation he had had with De Fois, the French Ambassador : “From this purpose we fell in talk of the pastimes that were the Sunday before, when the Lord Robert, the Lord John and others ran at the ring, six against Six, disguised and apparelled, the one half like women, the other half like strangers in strange masking garments. The Marquis [d’Elboeuf, the Queen’s uncle] that day did very well ; but the women, whose part the Lord Robert did sustain, won the Ring, The Queen herself beheld it, and as many others as listed.’

A few years later, when the Admirable Crichton was in Paris, we find him distinguishing himself as highly in the tilt yard as among the doctors of the University. Pennant, in his sketch of Crichton’s life, quotes from Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty the account of the famous disputation when Crichton caused notices to be affixed to the gates of the Parisian colleges and schools, inviting all the most renowned doctors of the city to dispute with him at the College of Navarre in any art or science, and in any of twelve languages, on that day six weeks ; ‘ and during all this time, instead of making a close application to his studies, he minded nothing but hunting, hawking, tilting, cards, dice, tennis, and other diversions of youth.’ ‘Yet on the day appointed he met with them in the College of Navarre, and acquit himself beyond expression in that dispute, which lasted from mine till six of the clock.” But still, after all this hard work, “he was so little fatigued with that day’s dispute that the very next day he went to the Louvre, where he had a match of tilting, an exercise in great request in those days; and in the presence of some princes of the Court of France, and a great many ladies, he carried away the ring fifteen times on end, and broke as many lances on the Saracen.” No wonder that “ever after that he was called the Admirable Crichton!

Echard, in his ‘History of England’, says that Charles the First was ‘so perfect in vaulting, riding the great horse, running at the ring, shooting with crossbows, muskets, and sometimes great guns, that if sovereignty had been the reward of excellence in those arts, he would have acquired a new title to the crown, being accounted the most celebrated marksman and the most perfect manager of the great horse of any in the three kingdoms. Gross flattery this probably was ; but many other passages might be cited to prove the fondness of the age for this and similar pastimes, by which, Burton tells us, “many gentlemen gallop quite out of their fortunes.’

Both the quintain— ‘common recreation of country folk’, and the ring— ‘disport of greater men, according to the “Anatomy of Melancholy’—appear to have gone out with the Stuarts in England, though in Scotland traces of tilting at the ring are found now and them in notices of country fairs and gatherings during the last century. A curious instance of this, where the pastime was cultivated as a preventive to intemperance that should endear it to Sir Wilfrid Lawson, is given in Sir John Simclair’s ‘Statistical Account of Scotland, in 1798.’ An old Perthshire society, the Fraternity of Chapmen, held their annual meeting for the election of their ‘Lord, or president, in the parish of Dunkeld. After the election the members dined together, and after dinner, the minister of the parish tells us, “to prevent that intemperance to which social meetings in such situations are sometimes prone they spend the evening in some public competition of dexterity or skill. Of these, riding at the ring (an amusement of ancient and warlike origin) is the chief. Two perpendicular posts are erected on this occasion, with a cross beam, from which is suspended a small ring; the competitors are on horseback, each having a pointed rod in his hand, and he who at full gallop, passing betwixt the posts, carries away the ring on his rod gains the prize.’

In recent years running at the ring has again become popular, especially at military sports, where the pastime, along with tent-pegging, its brother-sport from the East, cultivates quickness of eye and hand, and management of the charger among our cavalry, exactly as the old quintain and ring were designed to do among our ancestors eight centuries ago.

Macgregor, Robert, Belgravia: A London Magazine, vol. 38, (), pp. 316-320

1880

Obstructions are raised by the bride’s friends to prevent the bridegroom’s party from coming to her house ere the bride can be approached. Sometimes a mock battle on the road is a feature of the racing to church. The obstructions placed in the road in former days included the Gwyntyn, a sort of game of skill which seems to have been used by most nations in Europe, called in English the quintain. It was an upright post, upon which a cross-piece turned freely, at one end of which hung a sand-bag, the other end presenting a flat side. At this the rider tilted with his lance, his aim being to pass without being hit in the rear by the sand-bag. Other obstructions in use are ropes of straw and the like.

Sikes, Wirt, British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends, and Traditions, (London, 1880), Chapter 6; (Boston, 1881), pp. 306-314.

1882

MARRIAGE CUSTOMS.

The marriage customs of the Welsh have been treated by several writers at more or less length, but not I suspect, exhaustively by anyone. In the various accounts which have come under my notice I do not remember to have seen mention made of the following. One of the sports proper to the wedding day was the game of Chwintan. A pole was set in the ground, and a plentiful quantity of tough sticks set about it all cut to a certain length. The game was to break these sticks upon the pole in a swift and dexterous manner, and the bridegroom and his company, went in for a good deal of rough exercise on this auspicious day in order to test who was the gwr goreu amongst them.

J., D., Bye-gones, (November, 1882), p. 151

1888

Marriage Customs.

There is one peculiar custom, called Quintain, still observed sometimes in connection with weddings. It is a faint survival of the ancient Gwyntyn (literally, the Vane), corrupted in English into Quintain. This and other marriage customs are thus described by the Rev. Peter Roberts, Cambrian Popular Antiquities, (1815), p. 162.

“On the day of the ceremony, …singing to the harp and dancing prolonged the entertainment to a late hour.”

All these customs formerly prevailed, it seems, at Llanbrynmair, but the only thing that now remains is that on the return of a wedding party from church or chapel, children draw a rope across their path, and their further progress is stopped until they give a small gratuity to those who have put up the Gwyntyn.

A story of a lost bride, similar to the well-known incident recorded in the “Mistletoe bough”, is related in connection with the old Rhiwsaeson family.

Williams, Richard, History of the parish of Llanbrynmair, Montgomeryshire Collections, vol. 22, (1888), pp. 322-324

Reviewed with extracts in Bye-gones, (7 Nov, 1888), p. 263

1888

THE QUINTAIN IN WALES

I believe the sport known as “gwyntyn” is still practised in parts of South Wales. It used to be practised at weddings about Carmarthen and Brecknock. … The Welsh have derived the name of the sport from the nature of the game. An iron post with a cross bar used to be erected on the road near the bride’s house. A sandbag was suspended at one end, and at the other the men rode full pelt, striking the boards, and sending the sandbag flying round at such a rate that they felt the draught from its force waving their hair, and had hardly time to clear out of the way. It was thus called “Y Gwyntyn.” I am rather inclined to think that the sport obtained its name from quintus, because the Romans practised it every fifth year among the Olympic games.

Last century and the beginning of this it was practised in South Wales in the following manner :—

On the wedding day the bridegroom, with a large company, went on horseback to fetch his bride from her father’s house, whence he escorted her to church, accompanied by another parry of his own friends. When the ceremony was over, on their way home, a spot was chosen near the road side, where some planks, about six feet high, were fixed side by side. Long sticks were distributed to each of the young men who were disposed to take part in the sport. These sticks they grasped near the middle, resting one end under the arm, and then rode full speed towards the planks, striking the sticks against them with all their strength and skill in order to break down the erected barrier. There was neither sack nor sand in it according to this description of the game, but probably this was a modernised version of the quintain.

This old stanza describes the old form :—

Gorau gwaith i lewddyn,

Pan gyntaf êl trwy’r gwyntyn;

Ei farch dewr, cyflym, yn ddinag,

A’i ceidw rhag y cwdyn.

Thomas, Glanffrwd, (St. Asaph Vicarage), ‘The Old Cymry and Cultivation of Physical Strength, Fast Running, etc.’, Cymru Fu, (14 April 1888), p. 154

B., G.H., Bye-gones, 23 September, 1896, p. 435

1891

Gosodid y gwyntyn i fyny gan rai, yn gynwysedig o bost unionsyth, ac ar ei ben drosol cyfled a’r heol, yn troi yn rhydd ac yn rhwydd ; ar flaen y trosol, crogid cẁd wedi ei lanw â thywod, a’r pen arall yr oedd astyllen dew wedi ei sicrhau. Yr oedd y gwr ymgymerai â phasio yn gorfod taro yr astell; ac os na byddai mor ddeheuig ag i allu gwneuthur hyny, goddiweddid ef a’i farch gan y cŵd a’r tywod, ac efallai, ei daflu i’r llawr, yn mhlith chwerthiniad y dorf o’i gwmpas. Yn yr hen oesoedd, byddai gwylio manwl gan y blaid amddiffynol ar y modd y byddai yr ymosodwyr yn myned heibio y gwyntyn ; ac os dygwyddai iddynt wneyd hyny yn llwyddianus, hwyrach na chelent hèr i brofl eu medr yn un neu ragor o’r pedair camp ar hugain.

(The gwyntyn was set up by some, made up of upright mail, and at its top of a rolling road and the road, turning freely and easily; at the front of the trolley, a code filled with sand was hung, and the other end a thick obelisk had been secured. The pass-catcher had to hit the board; and if he were not as adept as he could do that, he would be overtaken and ridden by the dog and sand, and perhaps thrown to the ground, amid the laughter of the crowd around him. In ancient times, the defending party would watch closely how the attackers passed the wind; and if they happened to do that successfully, they might not be able to prove their skill in one or more of the twenty-four sports.)

E., S., Y Frythones, (Gorffennaf, 1891), tt. 204-208; (Hydref 1891), tt. 311-314

1910

Cwinten A rope covered with thorns used for throwing across a road at weddings, to stop the wedding party on their way from church, for the purpose of extracting a ffwtin (q.v.) from them.

Ffwtin: A toll or charge which a novice pays on being initiated into anything, also any money paid by a person for some kind of privilege = footing.

Morris, William Meredith, A Glossary of the Demetian Dialect of North Pembrokeshire, (1910)

1911

Another common practice in connection with the weddings in Wales, and still prevails in some places, was known as Chaining or Halting the Wedding. As the young husband and wife were driving home from Church at the end of the wedding ceremony they would find the way obstructed by ropes stretching the road, covered with flowers, and ribbons, and evergreens, or sometimes blocked up entirely by thorns. It is said that this was intended as the first obstacle in married life. Ropes in some cases were made of straw, and the young couple were not allowed to pass without paying a footing to the obstructors, and then the barrier was removed amidst a general hurrah. This chaining or halting the wedding was known in many parts of West Wales as “codi cwinten,” or to set up a quintain.

In ancient times Guintain seems to have been some kind of a game of skill in vogue among several nations; it consisted of an upright post, on the top of which a cross bar turned on a pivot; at one end of the cross hung a heavy sand bag, and at the other was placed a broad plank ; the accomplished cavalier in his passage couched his lance, and with the point made a thrust at the broad plank, and continued his route with his usual rapidity, and only felt the “gwyntyn,” or the “air” of the sand bag, fanning his hair as he passed. … [ellipsis in the original] The awkward horseman in attempting to pass this terrific barrier was either unhorsed by the weight of the sand bag, or by the impulse of the animal against the bar found his steed sprawling under him on the ground.”

Davies, Jonathan Ceredig, Folk-lore of West and Mid-Wales, (1911), pp. 16-39

1969

Of course, the ancient custom of obstructing the happy pair with rope stretched across the road is still maintained. [cwyntyn]

Extracts from a farmer’s account book in Lewis, E.T., Mynachlog-ddu, A Historical Survey of the Past Thousand Years, (1969), p. 83

2007

The Quintain

Martin, Neill, The Form and Function of Ritual Dialogue in the Marriage Traditions of Celtic-Language Cultures, (New York, 2007), p. 151